In Madurai,

city of temples and poets,

who sang of cities and temples,

every summer

a river dries to a trickle

in the sand,

baring the sand ribs,

straw and women's hair

clogging the watergates

at the rusty bars

under the bridges with patches

of repair all over them

the wet stones glistening like sleepy

crocodiles, the dry ones

shaven water-buffaloes lounging in the sun

The poets only sang of the floods.

He was there for a day

when they had the floods.

People everywhere talked

of the inches rising,

of the precise number of cobbled steps

run over by the water, rising

on the bathing places,

and the way it carried off three village houses,

one pregnant woman

and a couple of cows

named Gopi and Brinda as usual.

The new poets still quoted

the old poets, but no one spoke

in verse

of the pregnant woman

drowned, with perhaps twins in her,

kicking at blank walls

even before birth.

He said:

the river has water enough

to be poetic

about only once a year

and then

it carries away

in the first half-hour

three village houses,

a couple of cows

named Gopi and Brinda

and one pregnant woman

expecting identical twins

with no moles on their bodies,

with different coloured diapers

to tell them apart.

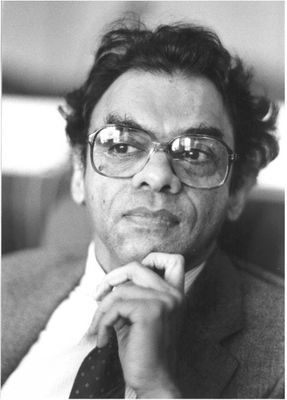

A. K. Ramanujan

Summary & Analysis

Attipate Krishnaswami Ramanujan (1929-1993) was an academic and creative writer from India who was highly honored during his career. Sometimes he wrote in English, but he also wrote in the Indian language known as “Kannada.” His poem “A River” is a realistic description of a river that flows (or sometimes does not flow) through the city of Madurai. The poem implicitly comments wryly on the lack of realism with which other poets have treated the same topic. At the same time, the poem itself seems ultimately a violation of the realism it at first seems to endorse.

The opening line immediately presents the main physical setting of the poem by mentioning the city of “Madurai.” By the end of the work, however, the relevance of the poem will transcend its relevance to this particular place. The speaker uses Madurai as his setting so that he can present detailed, concrete specifics rather than broad abstractions or generalizations. By the time the poem concludes, however, it will be obvious that the significance of his words transcends their significance for any specific city. This is ultimately a poem about the differences between writing that is realistic, conventional, and/or highly imaginative.

In line 2, Madurai is described as a “city of temples and poets,” making it sound like a place of great spiritual significance and associating it also with creativity and beauty. Its poets, indeed, have often sung of “cities and temples” (3), thereby celebrating places of great importance. Yet no sooner does the speaker make Madurai sound like a mythic, magnificent location than he immediately complicates (or even undercuts) this impression. He reports that each summer the city’s river—a river that might itself symbolize power, vitality, and energy—“dries to a trickle” (5), so that many of its normally hidden imperfections and unappealing aspects are suddenly visible, such as:

straw and women’s hairclogging the watergatesat the rusty barsunder the bridges with patchesof repair all over them....(8-12)

Part of the function of the present poem, then, is to reveal what is normally unseen and thereby deal with the full complexities of the river. The poet doesn’t hesitate to describe aspects of Madurai that conflict with the simplistic, romantic imagery with which the poem opened. This speaker and this poem present some of the full facts about Madurai, whereas other poets have tended merely to celebrate merely the beautiful, mystical aspects of the place.

To say this, however, is not to say that the speaker of this poem dwells only on the uglier aspects of the city or its river. Indeed, his descriptions of details that are not usually mentioned in other poems about Madurai are themselves sometimes beautiful. Thus he mentions the

the wet stones glistening like sleepycrocodiles, the dry onesshaven water-buffaloes lounging in the sun....(13-15)

Here his imagery is vivid and his similes (comparisons using “like” or “as”) are inventive and memorable. The river, although reduced to a mere trickle, can still provoke the imagination of at least this speaker, but most of the poets who have sung about the river “only sang of the floods” (16). Most previous poets, in other words, have presented only an incomplete and highly romanticized version of the river. They have failed to address the complete truth about the river and thus also about the city. They have preferred to emphasize beauty and power only, whereas the present speaker is willing to depict reality as it truly is, in all its full complexity.

The speaker now refers to himself in the third person (“He was there for a day” [17]), a technique also used in particularly memorable ways by (for instance) the Greek writer Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933). Use of this method gives the tone of the poem greater objectivity than if the speaker had said “I was there for a day.” It is as if the speaker wants to focus on the external conditions he describes rather than on his own personal reaction to them. This method will also make his later implied criticism of other writers seem therefore less a matter of personal sniping.

During his brief visit to the city on a day “when they had the floods” (18), the unidentified “he” heard people marveling about the specific transformations wrought by the rising waters. At first the changes seemed mostly benign, but then the speaker mentions that the flood

...carried off three village houses,one pregnant womanand a couple of cowsnamed Gopi and Brinda as usual. (24-27)

The flood, then, was both impressive and destructive, and the loss of the pregnant woman seems especially unfortunate. The rising river, which might normally be associated with life and renewal, is here associated with death—death not simply for the unfortunate cows but also for the equally unfortunate woman and the life inside her, life that is not even given a chance to truly, fully live. Yet even as the speaker describes this painful loss, he interjects some sly humor when he refers to the stereotypical name of the cows that also died in the flood. This mixture of understated humor and blunt realism is typical of the way this poem operates. Simple statements, in this text, are never allowed to stand; complexities of one sort or another are continually introduced. Just when we are mourning the loss of the pregnant woman, the speaker mentions two comically-named cows. One of the main points of this poem is to say what is not normally said and thus to be truer to the complex nature of reality than is often the case in works by other writers.

In this respect, the speaker of the present poem differs significantly from many of his peers. Other writers merely parrot the works of their predecessors. They write in highly conventional ways and therefore are neither fully truthful nor significantly original (28-29). They neglect to mention the uglier, less appealing aspects of reality, such as the loss of the pregnant woman (29-31). However, no sooner does the speaker imply that he is a realistic writer who sticks to the facts than he also immediately complicates that impression by offering pure speculation about the pregnant woman, suggesting that perhaps she had

...twins in her,kicking at blank wallseven before birth. (32-34)

Part of the effect of the poem, then, is to seem constantly surprising and increasingly complex as it develops toward its conclusion. The speaker repeatedly alters his tone and his perspective, and indeed later he speculates even more than he has already. Now he refers to

one pregnant womanexpecting identical twinswith no moles on their bodies,with different coloured diapersto tell them apart. (45-50)

Having at first implied that he is more truthful than other poets, he now presents himself as more inventive and literally imaginative than they. They follow stale conventions and merely repeat what has already been said. He, on the other hand, by this point in the poem is inventing and imagining details that no one could ever really know. In both ways—not only in his realism but also in his flights of imagination—he presents poetry that is more vivid, more compelling, more thought-provoking than the poems of his peers. Whether describing actual details (as when he depicts what lies beneath the river when it is merely a trickle) or whether inventing details he cannot possibly know (such as the precise details about the wholly imagined twins), the speaker of this poem seems a more complex and intriguing writer than other poets who have written about Madurai and its fabled river. Ultimately the poem is less about either the city or the river than about the ways writers can deal (or not deal) with reality and fantasy.

0 Comments